Before and After: Movements

A Look at Our Movement Restorations

A Note Concerning How We rebuild Clock Movements

And What You Will Be Seeing

Generally speaking, when a movement is rebuilt, overhauled or restored, when done properly, it will include the following work. The movement will be disassembled, cleaned, all the pivots burnished, and all the bearing surfaces restored to proper size and location. Every part will be examined for any significant defects and repaired, rebuilt or replaced if necessary. The levers in the clock will have all their acting surfaces polished to remove any ruts caused by their action. In addition, the escapement pallets will also have their acting surfaces restored and the escapement geometry corrected. The ratcheting mechanism on the main wheels will be checked for proper operation, resurfacing or replacing damaged clicks and or click springs. The mainsprings will be cleaned, checked for damage and regreased unless it is determined that the mainsprings need to be replaced. If it is a weight driven clock, the cables will be replaced. The clock will then be reassembled, synchronized, the levers adjusted for most efficient operation, the movement oiled and then installed in the case and tested for at least a week.

Most “clock repair people” will only do a few of these steps, usually just two, cleaning the clock and installing new bushings in the worst of the worn bearings. Almost all of the other things in the list above are simply ignored.

Unfortunately, most of the work we are doing cannot be seen in just a few photos and without extreme close ups. That is not the purpose of this page. If you would like a more detailed description with photos of our overhaul process, please visit our “Clock Movement restoration” page.

What you will see however, is how clean the movements look after the rebuild. How shiny the movement looks has very little bearing on how well the clock runs and for this reason, many shops do not spend any time trying to make the movement “look good”. We spend a bit more time doing this because we are trying to offer a superior service.

We have created this page because the vast majority of our work is never seen by the clock owner since the restored movement is hidden behind the clock’s dial. This page is for those who would like to see the transformation that occurs between a dirty, worn-out movement and a freshly rebuilt one using before and after photos of the many different types of clock movements we work on.

While We Examine Our Clock Movement Restorations, we will also Offer a brief history of mass-produced American clock movement development.

In the first section, we have placed the American made clock movement types in chronological order by age and development. Although clock movements were being made in America in the early 1700’s they were not mass produced until around 1800. For this reason, we will begin in 1800 with the first truly mass-produced clocks, the wood works movements made by Eli Terry.

Thirty Hour Weight Driven Wooden works Movement

The first mass produced American movements were made mostly of wood, including the gears and the plates. The gearing had steel pivots, but those steel pivots turned in wooden bearing holes! Seems like a stupid idea for a machine, but these clocks turned out to be quite durable and can still be made to run today. Although wood works clocks were known to have been hand made in America as early as 1750, they were not mass produced until 1800, and continued to be made until around 1840 when brass clock movements began to be produced in larger numbers.

Up until this time, clocks were made to order, out of brass and steel, one at a time. Because of this, no two clock movements were exactly the same, meaning the parts were not interchangeable. Making the parts out of wood, instead of brass and steel, enabled them to cut multiple pieces simultaneously and make them exactly the same. This concept was introduced by a man named Eli Terry. This “assembly line, all parts the same”, mentality would eventually be copied by Henry Ford to make automobiles.

I do not have a Photo of this clock movement before we restored it, but I do have these pictures from after the restoration. The first picture is a close up showing the fully cleaned, pivots burnished, replacement wood bearing restoration we performed. We are able to install the wooden bushings in a way that make it almost impossible to detect from the outside of the plates, maintaining the original look of the movement. The brass gear near the top center is the only metal gear in the clock. This was necessary due to the stress that this gear is under compared to all the other gears. The second photo shows the weights and part of the original paper label under the movement. Right under the bell you can see that it says, “Patented by Eli Terry”. The third photo shows the movement in the case without the dial mounted. This style of case is called a “Half Column and Splat”. This clock would date near 1835.

Wood Works Movement

Half Column and Splat Case

Weight Driven Wooden Works Floor Clock Movement

The clock movement above is from a mantle clock. The one shown below is from a tall case clock. Once again, I do not have a “before” photo, just a photo from after my restorative work was completed. I show this photo mainly so that you can see the inside of the clock movement where the wooden gears can be seen.

Eight Day Weight Driven Strap Movement

The earliest American clocks were all weight driven as the Americans had not yet developed the capacity to make their own mainsprings. Also, note that the front and back plates were not cut from a solid piece of brass, like movements that came a bit later. These plates were made by riveting several pieces of thin brass straps to make a larger “plate”. This was necessary because the early Americans were unable to produce sheets of brass large enough to form a complete plate. This movement was likely manufactured in the 1830’s during a transitionary period between the mass production of wooden works movements and brass plates stamped from a single sheet of rolled brass.

Before

After

Another Eight Day Weight Driven Strap Movement

Another “strap” movement from 1830 to 1860 era.

The cased clock in the middle is typical of that which would house a movement like this one. This style of case was popular from early 1850’s through the 1870’s and is often called a “Double Decker” or “column and Cornice”.

Before

After

Individual parts of a strap movement

Each piece is checked for deficiencies and restored prior to reassembly. These pieces have already been cleaned and buffed.

Column and Cornice Double Decker

Early American Eight Day Weight Driven Strike Mantle Movement

By around 1860 the American movement manufacturers were able to roll out brass sheets large enough to make a clock plate out of a single solid sheet of brass. Therefore, they transitioned out of the “strap” movements and into one piece clock plates. The plates could have remained solid without the rectangular holes you see below. But there are two reasons why they did not do this. The first reason was to save valuable material. by cutting out the areas that technically were not necessary, they would have smaller brass sheets to make additional clock parts from. The second reason is that it gave them greater access to the internal mechanical components so they could be adjusted more easily after assembly.

The clock case in the middle photo is an Eight Day, Weight Driven, Ogee, Striking Clock. The term Ogee is a reference to the curved shape of the outer frame of the case. During this same time frame, Ogee mirrors and Ogee picture frames were also popular. Because the clocks were weight driven, the cases had to be large enough to allow sufficient room for the weights to drop over the course of a complete week.

Before

After

Common Case Style for this type of movement. This is an 8 Day Ogee Clock

Thirty Hour Weight Driven Clock Movement

This is the little brother of the larger eight-day clock above. Because the movement and the weights were smaller and the needed drop of the thirty-hour weights was not as long, the cases could be made smaller and therefore cheaper. Thirty-hour clocks were much more popular for that reason. Most families could not justify the extra 50 cents or so needed to buy the larger eight-day version just for the convenience of a once per week wind when it only takes a few seconds to wind the clock every day. These clocks were popular between the 1860’s and 1880’s, making them close to 150 years old!

The photos below show the before and after photos of a movement we restored. The photo on the left was taken before the repair began. You can see several of the gears are laying loose inside the case. The clock is very dirty and worn badly. The photo on the right was taken after the restoration was completed.

The case in the center is the cousin of the Ogee clock shown above. it is a thirty-hour Half Column clock. They call it that because, once again, the manufacturers, looking for ways to save money and make the clocks less fragile, took a single, full column, sawed it down the middle and were able to give the appearance of two columns for the price of one. The thirty-hour cases, both Ogee and Half Column, were about 25% smaller than the larger eight-day cases.

Before

After

Half Column Clock Case

Early American Seth Thomas Spring Driven “Lyre” Movement

By 1840 the Americans were making inferior mainsprings from brass. These springs did not maintain their “springiness” very long, making them less than ideal for reliable timekeeping over the course of a full week as they got older. Because of this, these springs were not used in clocks for very long, making them quite rare compared to clocks with steel springs. By 1850 they were making more reliable mainsprings from steel and by 1880 the sale of spring driven clocks had overtaken the more expensive weight driven clocks. Spring driven clocks could be housed in smaller, lighter cases making them cheaper to produce and ship.

this Seth Thomas eight-day striking mantel movement, from the 1870’s, is quite unique due to the very unnecessary “lyre” shape of the plates. Unnecessary yes, but for those who appreciate both clocks and art, this movement is a thing of beauty, indeed. Unfortunately, a beauty, rarely, if ever seen by the owner of the clock since the movement was hidden behind the dial. You might guess that this movement did not stay in production very long, and you would be right, as it was more expensive to make than a plainer, smaller set of clock plates.

The before and after photos below are not as dramatic as most since the before photo is of a movement, that although worn badly, was not very dirty. It is a shame that the movement shown below is missing the original “Geneva” stops. It is likely that a previous repairman removed them since they did not understand how to install them properly.

The clock case in the middle photo is a Seth Thomas Parlor clock, typical of that which would contain a movement like this. This upgraded, walnut case is the often-older brother to the more common, oak “Kitchen” clock.

Before

After

The Various Parts of a Lyre Movement after cleaning and buffing

Common Case Style For This Movement

Early American Seth Thomas Spring Driven “Hip” Movement

This movement is often called a “hip” movement due to the shape of the upper section of the plates. Although this style was developed as early as 1877, this movement is from the early 1900’s. Surely, not as pretty as the Lyre movement shown above. Most movements would eventually make their way to a simpler rectangular shape.

Before

After

Seth Thomas #89 Spring Driven Movement

We cannot end this run of Seth Thomas movements without mentioning the venerable Seth Thomas #89 movement, the work horse of the Seth Thomas movement line up. Seth Thomas had developed over a hundred movement designs over the years, but this one, and its variations, are the ones we see most often in Seth Thomas mantle clock cases. The 89 went through 15 design changes between 1907 and 1936 when the line was ended.

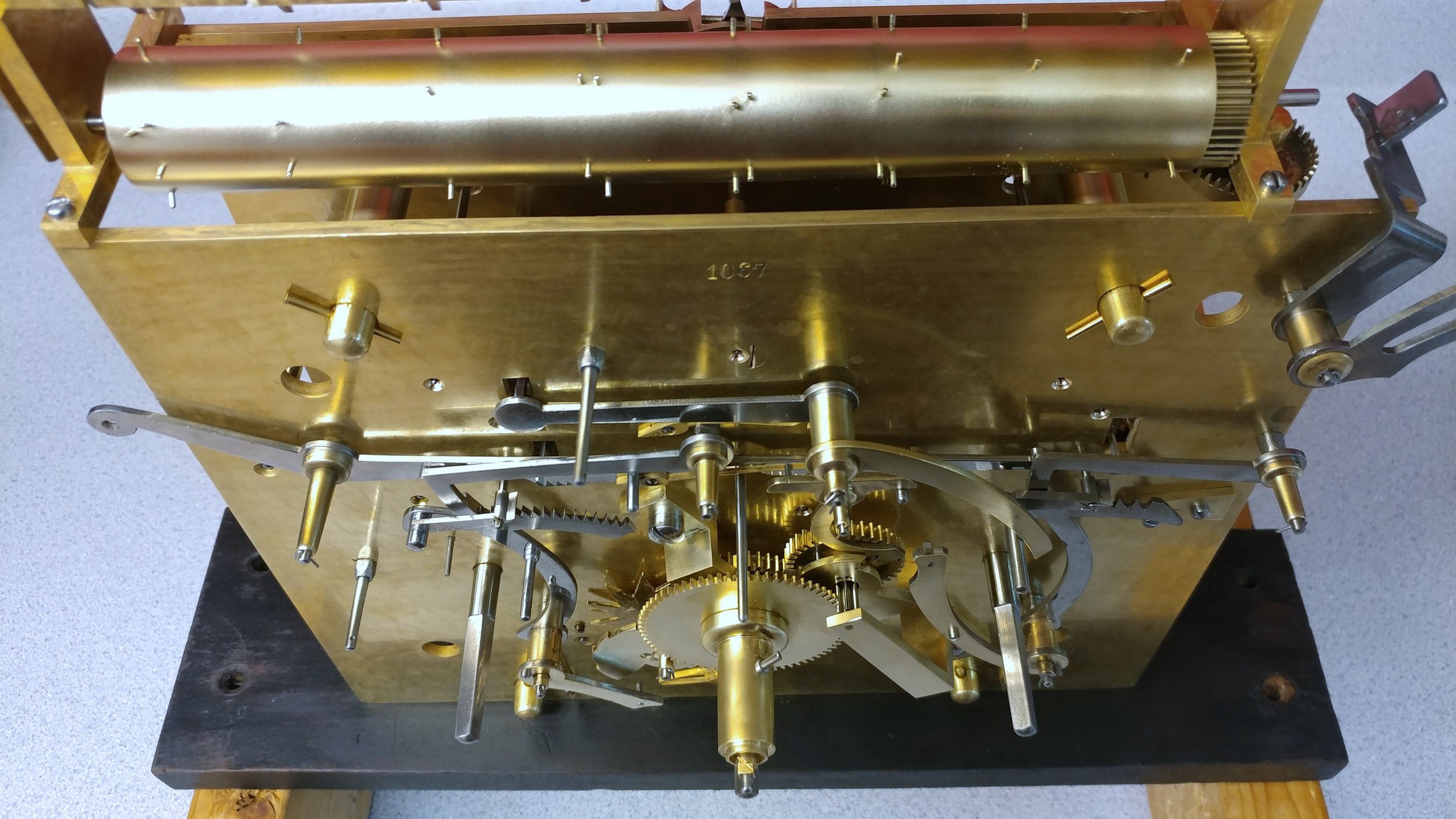

Front View of Movement

Rear View of Movement

Early American Kroeber Eight Day Mantel Strike Movement

In this example we can see the simpler rectangular plate design. This one was made by Kroeber. They were in business from about 1870 to 1900, not near as long as many of the early American Companies.

Before

After

Ansonia Eight Day Spring Driven Movement

These are photos of a common spring driven Ansonia movement from around 1900. you can see that these plates are a bit more interesting than the simpler rectangular shape.

Before

After

This ends the section on American movement development.

By the 1940’s many of the early American clock companies were going out of business. Seth Thomas, Ingraham and Ansonia were a few that managed to hang on longer than most. Even though these few hold outs were still making their own cases here in America, movement manufacturing was quickly shifting from “Made in America” to “Made in Germany”. Chelsea Clock Company, a company specializing in Ship’s Bell clocks, is the last manufacturer of American made clock movements and solid brass American cases still in business today. Howard Miller and Ridgeway (owned by Howard Miller) are the last substantive American manufacturers of American made clock cases in America. They do not use Amercian made movements but German imports instead.

Antique Cuckoo Clock Movement Restoration

Cuckoo clocks, along with their unique case design, “striking and or chiming” arrangement and the “animation” of dancers, water wheels, lumberjacks, beer drinkers etc. places them in a category all their own. In the modern era, obtaining a replacement movement is frequently the best option for repair when the original movement wears out. For antique cuckoo clocks, it is best to restore the original movement. Below are two examples.

Antique German cuckoo Clock Movement Restoration

The early cuckoo movements used brass plates that were cast in a mold instead of the flat, rolled brass sheets used in modern cuckoo manufacturing. The cast brass plates were thicker and harder, making the early cuckoo clock movements more durable.

Before

After

Antique German Cuckoo and Quail Movement

These movements were more complex than the one shown above. A cuckoo and quail clock plays a quail pattern at the quarter hours followed by the cuckoo “strike” at the top of the hour and on some, a single cuckoo “strike” at the half hour.

Before

After

Antique English Bell Striking Fusee Mantel Clock Movement

These very high-quality striking clocks were known as “Fusees”. Fusee clocks had a unique way of equalizing and increasing the efficiency of the mainspring that drives the movement. Basically, it was designed to allow the clock to run more accurately and the strike to occur at a more consistent speed throughout the run of the unwinding mainspring. The fusee system is rarely if ever used in modern clockmaking today due to the expense of manufacturing the more complex design. With the increased quality and consistency of modern mainsprings, the advantage of the fusee system began to diminish.

Before

After

Antique French Striking Mantel Clock Movement

The French made very high-quality movements that were often much smaller than those made in other countries. Their movements tended to be extremely well engineered, very durable, contain very small gearing with extremely fine teeth and were also frequently more difficult to operate by the average clock owner. Although the French had many movement designs, the round clock movement, shown below, is the type of French movement most often encountered.

Before

After

Exploded View of French Movement after cleaning and buffing